Want to play college baseball? This weekend, you must do this.

Watch College Baseball

The NCAA Regionals are played continuously from Friday to Sunday on ESPN U, ESPN 3, and the SEC Network. Can’t make it because you have games all weekend? DVR a few of the games and watch them Sunday night.

Take this yearly opportunity to learn about your potential competition. Analyze the physical attributes of each player, how they play the game, how fast they run, how hard they throw. So often I work with players who want to play college baseball, but have no idea what the talent pool is like at that level.

Check out the rosters of some of the known powerhouses. For instance, Texas has only 4 players listed under 180lbs. Of the 17 pitchers on their staff, Texas has only 1 that is under 180lbs, and he is a freshman. Weight is not the end all be all for baseball players, but it is absolutely one indicator of how well someone is built (assuming the athletes are lean). Adding muscle mass is one of the easiest ways to increase mph on the mound, decrease injury risk, and raise your overall athletic potential.

Why bodyweight is important for pitchers

The speed of the college game is often surprising for high school athletes, especially at the high echelon DI programs. In 2013, Perfect Game published this list of the fastest high school sophomores, juniors, and senior 60 yard dashes.

Averages: High School Senior 7.31 | Junior 7.44 | Sophomore 7.56

Top Performers – 60-Yard Dash – Class of 2014

| RK | Time | Name | Event | School | City | State |

| 1 | 6.28 | Carl Chester | National Showcase | Lake Brantley | Longwood | FL |

| 2 | 6.31 | Denz’l Chapman | National Showcase | Serra | Los Angeles | CA |

| 3 | 6.35 | Jared McKay | Southeast Top Prospect Showcase | Chamblee Charter | Stone Mountain | GA |

| 4 | 6.36 | Evan Holland | Mid Atlantic Top Prospect Showcase | Timber Creek | Erial | NJ |

| 5 | 6.37 | Jack Flaherty | National Showcase | Harvard-Westlake | Burbank | CA |

| 6 | 6.42 | Clay Lane | Sunshine South Showcase | Kaufman | Kaufman | TX |

| 7 | 6.43 | Michael Gettys | National Showcase | Gainesville | Gainesville | GA |

| 8 | 6.44 | Derek Hill | National Showcase | Elk Grove | Sacramento | CA |

| 9 | 6.45 | Connor Brady | South Top Prospect Showcase | Plano Sr. | Plano | TX |

| 10 | 6.46 | Matthew Collins | National Showcase | Memorial | Houston | TX |

| 10 | 6.46 | Trenton Kemp | National Showcase | Buchanan | Clovis | CA |

| 12 | 6.47 | Troy Stokes, Jr. | National Showcase | Calvert Hall College | Baltimore | MD |

| 12 | 6.47 | Stone Garrett | National Showcase | George Ranch | Sugar Land | TX |

| 14 | 6.48 | Tristan Rojas | Sunshine Northeast Showcase | James Monroe | Bronx | NY |

| 15 | 6.49 | Landon Morgan | South Top Prospect Showcase | Lubbock Christian | Levelland | TX |

| 15 | 6.49 | Giovanni Abreu | National Showcase | George Washington | New York | NY |

| 15 | 6.49 | Jeren Kendall | National Showcase | Holmen | Holmen | WI |

| 15 | 6.49 | Alexis Pantojas | Caribbean Top Prospect Showcase | Puerto Rico Baseball Academy | Vega Alta | PR |

Top Performers – 60-Yard Dash – Class of 2015

| RK | Time | Name | Event | School | City | State |

| 1 | 6.44 | Satchel McElroy | Jr National Showcase | Clear Creek | League City | TX |

| 2 | 6.45 | Demetrius McAtee | South Underclass Showcase | Parkway | Bossier City | LA |

| 3 | 6.46 | Alex Shaver | Jr National Showcase | George Ranch | Sugar Land | TX |

| 3 | 6.46 | Bakari Gayle | Jr National Showcase | Martin Luther King, Jr. | Stone Mountain | GA |

| 5 | 6.50 | Eric Cole | South Underclass Showcase | Southlake Carroll | Southlake | TX |

| 6 | 6.51 | Connor Smith | Ohio Valley Showcase | H.H. Dow | Midland | MI |

| 7 | 6.54 | Roman Millem | Ohio Valley Showcase | North Oldham | Prospect | KY |

| 7 | 6.54 | Jimmy Herron | Jr National Showcase | La Salle College | Harleysville | PA |

| 9 | 6.55 | Daniel Little | National Underclass Session 3 | Lexington Catholic | Nicholasville | KY |

| 10 | 6.57 | Demi Orimoloye | Jr National Showcase | St. Matthew | Orleans | ON |

| 10 | 6.57 | Bakari Gayle | Southeast Top Prospect Showcase | Martin Luther King, Jr. | Stone Mountain | GA |

| 12 | 6.59 | Tyler Williams | Jr National Showcase | Raymond S. Kellis | Peoria | AZ |

| 12 | 6.59 | Shane Selman | Sunshine South Showcase | Alfred M. Barbe | Lake Charles | LA |

Top Performers – 60-Yard Dash – Class of 2016

| RK | Time | Name | Event | School | City | State |

| 1 | 6.62 | Vincent Ramos | Caribbean Underclass Showcase | Colegio Bautista | Toa Baja, Levittown | PR |

| 2 | 6.64 | Nicholas Rowland | Mid Atlantic Underclass Showcase | Chestnut Hill Academy | Blue Bell | PA |

| 3 | 6.67 | Ryan Mejia | Sunshine East Showcase | Alonso | Tampa | FL |

| 4 | 6.72 | Matthew Meisner | Sunshine Northeast Showcase | Salem | Salem | NH |

| 5 | 6.78 | Christian Moya | California Underclass Showcase | Bishop Amat | Chino Hills | CA |

| 6 | 6.79 | Cameron Locklear | Atlantic Coast Underclass Showcase | Jack Britt | Fayetteville | NC |

| 7 | 6.82 | Tyrik Jones | Southeast Underclass Showcase | The Galloway | Stone Mountain | GA |

| 8 | 6.83 | Corbin Bice | Southeast Underclass Showcase | Chilton Co. | Clanton | AL |

| 9 | 6.83 | Aidan Elias | Ohio Valley Showcase | Sayre | Lexington | KY |

| 10 | 6.84 | Kace Massner | Midwest Underclass Showcase | Burlington Community | Burlington | IA |

| 11 | 6.85 | Isaac Collins | Midwest Underclass Showcase | Maple Grove | Maple Grove | MN |

| 11 | 6.85 | Austin Bodrato | Sunshine Northeast Showcase | St. Joseph Regional | Northvale | NJ |

| 11 | 6.85 | Ashton King | Atlantic Coast Underclass Showcase | Christiansburg | Christiansburg | VA |

Source: http://www.perfectgame.org/Articles/View.aspx?article=9177

As you can see, the average senior in high school ran a 7.3 60-yard dash, which is not overly impressive. That 7.3 average is largely made up of athletes who will never step foot on a college ball field. Of high school varsity baseball participants only 5.6% will play at the collegiate level.

Only 5.6% of high school baseball players ever make a college team. As a high school athlete, are you REALLY outworking the other 95%?

— Josh Heenan (@josh_heenan) May 25, 2015

What is impressive is the fastest sophomore ball players run between a 6.44 and 6.85. That is blazing fast for an underclassman. To even come close to breaking the top 15 for the senior class you must run under a 6.5, which is plus speed for an MLBer.

So how do you stack up?

Not sure how hard you throw? Get on the gun at your next outing.

Not sure how fast you run? Go to a track and video tape your 60 yard dash. Video does not lie, handheld timers do.

Be analytical with the games you are watching this weekend and see how you would compare against the competition and what aspects of your game need the most work.

Have questions or comments about playing at the next level? Leave a comment below.

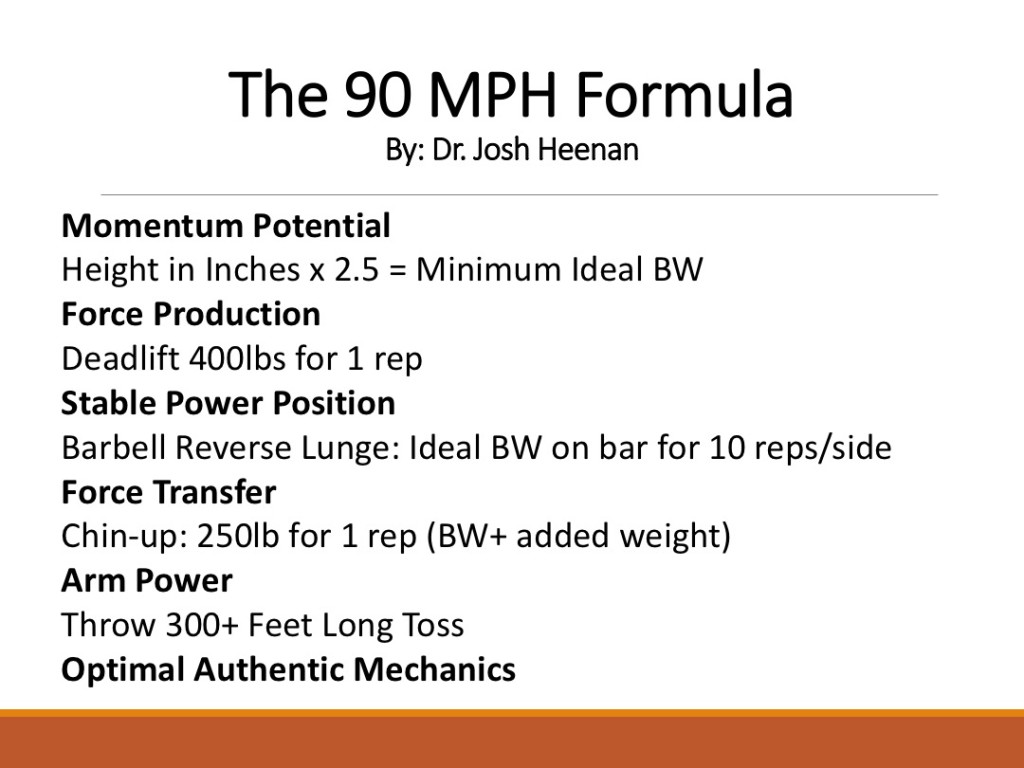

Qualities Needed to Throw 90+MPH

If I am a 17-year-old, 165 lb pitcher, and can consistently throw 79-82 MPH for my fastball, if I get up to 200 lb with 12% or less body fat, should I be able to throw in mid 90s or at least the 90s?

Bodyweight has been directly correlated to fastball velocity.

Relationships between ball velocity and throwing mechanics in collegiate baseball pitchers

I touch upon this point here: “As a general rule of thumb, our Sacred Heart pitchers will gain 2-4 mph a season during their 4 years in college. As much as I would love to say it’s just training, there are numerous reasons why we get increased ball velocity each year including mechanical improvement, growth of body due to puberty, increased muscle mass, and improved body awareness/muscular coordination. The interesting trend is that most of our athletes tend to add anywhere from 5-15 lbs of bodyweight each year. Does 5-15lbs = 2-4mph on the mound? Maybe.”

Why All Baseball Players Should Be Using Creatine

With my pitchers, we have the following hierarchy/system:

1) Mechanics Rule All: Increase mechanical efficiency your energy leaks will decrease and velocity will go up.

2) Increase General Strength: Building a foundational base strength is not only performance enhancing, but done properly will decrease the risk of injury.

3) Increase Muscle Mass: More muscle mass, the more potential to apply force.

4) Increase General Force Production (e.g. Power): Allows us to tap into more high threshold motor-units to produce more force and increase IIx muscle fiber.

5) Increase Skill Specific Power: Explosive training in a transverse plane. This could be med ball throws, weighted or under-weighted ball throws, long toss, flat ground or even mound work.

We have had many mid 90MPH pitchers (injury free to boot) as well as some whom have touched 99+MPH. Some of these athletes have gained upwards of 50lbs of very clean weight (still viable abs) in less than a year. Everyone is different based on genetics, work ethic, movement capabilities, diet etc.

If you are mechanically efficient, have relatively long levers and can increase body mass to 200lbs and force production increase proportionally it is very possible. This information as well as programming for this goal is covered in detail in Building the Perfect Pitcher.

Move Fast, Throw Hard, Live Well- Little League Curveballs and Youth Weight Training

This weeks post I am going to share a readers question and my response about weight training his younger athlete. If you have a question you would like answered feel free to shoot me an email.

Enjoy!

Q:

What would you recommend for a 13 yr old 7th grader, honestly? I am not wanting him to do more than hi-rep, bodyweight exercises at most. He’s 5’9” (and growing), 110 lbs. throws pretty hard – has a nice arm, and I want to keep that intact. Staring the travel ball with a good, established organization in IL this year…what are your thoughts on throwing curve balls, if taught by a former pro pitcher, etc? (I am leery of that).

A:

As I said in the webinar, if you can play organized sports, you can train (and its safer!). High rep stuff is fine, but that’s where we usually see injuries because of fatigue and poor form. Moderate weights would be a better option for him. Move well and then move higher weights.

Here is my take on youth curveballs; research wise if it’s being taught properly (mechanically efficient) there is not a huge chance of injury. That being said, there are a ton of bad coaches out there (not that his is bad–I have no idea), but being a former pro doesn’t automatically qualify you to be a “good” or well researched coach.

From what I have seen in the rehab and coaching world, poor progression of throwing (jumping up in intensity or mainly volume) too quickly leads to lots of issues. The kids who throw “too many curveballs” are usually the kids who cant compete with just a fastball. And as I have written about before, skipping on fall/winter baseball is a must.

At this point in my career, if my child was a pitcher in little league I would encourage fastball and change up location and speed, that alone will keep batters off balance. Once they start shooting through puberty (13-15 years), I would let them play with curveballs with a coach that is highly qualified. I grew up with a coach who said “never two curves in a row” for both practice and play. Great rules to help set-up hitters and stave away from overuse.

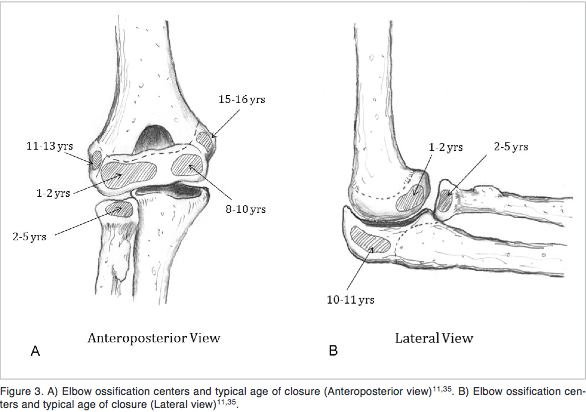

The image attached is a visual of when portions of the arm ossify. The medial epicondyle is the last to fully fuse and we should always proceed with caution.

On the other hand, Phil Rosengren does a great job at expressing why he thinks kids should be tough the curveball at a younger age. To be frank, I don’t disagree with any of his points. And to Phil’s credit, every athlete he has sent me has never had an elbow pathology.

Many people are racing for their kids to be on ESPN in the LLWS. I think they are racing the wrong race. I’ve had the opportunity to work with many kids whom have been on ESPN before the age of 13… some of what they are dealing with mentally are so unfathomable it’s disgusting. Not to mention some of the injuries I’ve seen especially from the “best” players on those teams.

Screening and Program Design for Baseball Players

The following video is a snippet taken from a seminar we held at Moore this past fall. It shows a few pieces of how we assess each athlete whom walks through our doors and how we design programs/lifestyle changes to fit their individual needs. Enjoy and Happy New Year!

Scribner Documentry

The past few months have been very busy at Moore, thus the lack of posting here. A few of my athletes have been featured recently with some very cool documentaries. Most recently, Troy and his brother Evan. Happy Holidays and enjoy the video!

Portraits : The Scribner Brothers from Manuel A. Santiago

Why Your Conditioning is Hurting Your Performance on the Mound!

By now, readers of this blog are familiar with the concept of the “well rounded athlete”—the athlete who focuses on the fundamentals of movement and conditioning in order to master the finer points of his sport. While I believe that all baseball players should embrace this philosophy, I urge pitchers to exercise particular caution in applying it. This is especially true with regard to distance running and pole running, two long-time staples in the pitching community. As I explain in the following paragraphs, these conditioning methods may harm a pitcher’s on-field performance more than they enhance it.

Common Misuses of Conditioning

The first misconception about distance and pole running is that they help to remove excess lactate from the blood after a pitching outing. This belief embodies a basic misunderstanding of the physiology of pitching. Pitching is a maxium effort burst movement that is repeated dozens of times over the course of a game. The burst motion of pitching relies on the phosphogen or ATP-CP system, which is regarded as a lactic anaerobic energy system because it neither uses oxygen nor produces lactic acid if oxygen is unavailable. In laymen’s terms this means that, contrary to popular belief, pitching does not increase blood lactate levels significantly. Therefore, “flush” runs designed to lower blood lactate levels merely expose pitchers to a decrease in power and increased risk of injury without bestowing any measurable benefit.1

Distance and pole running present other problems as well: a lack of neural adaptation (high powered nervous system output); limited or diminished strength gains; and an underdeveloped range of motion in portions of the lower body that are essential to the pitching motion. Holloszy and Booth produced the following paragraph while studying the biochemical adaptations to endurance exercise in muscle.

“The nature of the exercise stimulus determines the type of adaptation. One type of adaptation involves hypertrophy of the muscle cells with an increase in strength; it is exemplified in its most extreme form by the muscles of weight lifters and bodybuilders. The second type of adaptation involves an increase in the capacity of muscle for aerobic metabolism with an increase in endurance and is found in its most highly developed form in the muscles of competitive middle- and long distant runners, long distant cross country skiers, bicyclists, and swimmers. Although many types of physical activity can bring about varying degrees of both types of adaptation in the same muscle, it does appear that these adaptations can occur quite independently of each other in their most extreme forms. For example, the hypertrophied muscles of weight lifters do not appear to have increased respiratory capacity, whereas the muscles of rodents trained by prolong daily running, which have large increase in respiratory capacity, are not hypertrophied and show NO INCREASE IN STRENGTH”2

As I have discussed elsewhere, bodyweight is directly correlated to ball velocity. Distance running reduces an athlete’s fast twitch muscle fiber count and muscle mass, which leads to diminished overall body mass and ultimately robs a pitcher of crucial miles per hour on his pitches. However, there is good news even for pitchers who have unwittingly sacrificed body mass and velocity by doubling as distance runners. By using creatine as a dietary supplement, a pitcher can increase body mass both quickly and safely, and will likely reap the benefits in the form of increased ball velocity. I discuss this topic at length in my article “Why All Baseball Players Should Be Using Creatine.”

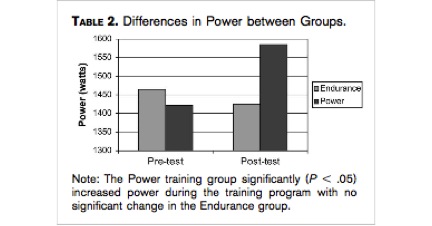

Further proof that pitchers should avoid distance running is offered in a tremendous article titled “Noncompatibility of Power and Endurance Training Among College Baseball Players.” This study split 16 Division I collegiate pitchers on the same team into 2 groups, both of which were tested before and after th season. The sprint group performed repeated maximal sprints ranging from 15 to 60 meters with 10 to 60 seconds rest between each sprint. Workouts were performed 3 days per week and consisted of 10–30 sprints. The second group (8 Pitchers) performed moderate- to high-intensity aerobic exercise (jogging or cycling) 3–4 days per week for 20–60 minutes per day (mainly poles). Over the course of the season, the sprint group increased power by ~20% while the endurance group decreased power by ~ 3%. That’s dramatic.3

In short, pitchers should think long and hard before incorporating distance and/or pole running into their training routines. Basic physiology suggests (and the research confirms) that these endurance-based practices jeopardize a pitcher’s power, muscle mass, and skill-specific endurance. Any pitcher intent on succeeding at the highest levels of the game should focus on building and maintaining muscle mass and fine tuning mechanics to optimize the power transfer between his wind-up and delivery. Ball velocity is, and always will be, the factor that separates the wheat from chaff.

Optimal Conditioning for Pitchers

Here are three options I use for conditioning for pitchers (all baseball players for that matter). Be sure to fit your workload and rest frequencies to the aerobic and muscular systems that you are working on.

- Sled Pushes

Sets of 10-40 yards. You can adjust loading parameters to meet your goals with regard to power, speed, and strength.Shout to @josh_heenan giving me that 700lb sled push for breakfast.

— John Michael Murphy (@MurphsLaws) November 11, 2013

- Flat Ground Sprints

Sets of 10-40 yards. You can play with the number of sets to fit your goal of repeated power. - Hill Sprints

Sets of 10-20 yards is sufficient. You can play with the number of sets to fit your goal of repeated power. Obviously the steeper the hill, the more you will hate life!

Conclusion

Just because a practice has become tradition does not mean that it is the best, or even a good way, to enhance on-field performance. Further research and anecdotal evidence will undoubtedly reveal even better ways than the ones I offer above to optimize a pitcher’s output. However, the next time a coach tells you to run poles or run a few miles, politely share this article with him and ask their opinion. I welcome any and all feedback, and I sincerely hope that this post is merely the start of a much larger conversation.

Works Cited

1. Potteiger JA, Blessing DL, Wilson GD. The physiological responses to a single game of baseball pitching. J Strength Cond Res. 1992;6(1):11–18.

2. Holloszy JO, Booth FW. Biochemical adaptations to endurance exercise in muscle. Annu Rev Physiol. 1976;38:273–291. doi:10.1146/annurev.ph.38.030176.001421.

3. Rhea MR, Oliverson JR, Marshall G, Peterson MD, Kenn JG, Ayllón FN. Noncompatibility of power and endurance training among college baseball players. J Strength Cond Res Natl Strength Cond Assoc. 2008;22(1):230–234. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e31815fa038.