Screening and Program Design for Baseball Players

The following video is a snippet taken from a seminar we held at Moore this past fall. It shows a few pieces of how we assess each athlete whom walks through our doors and how we design programs/lifestyle changes to fit their individual needs. Enjoy and Happy New Year!

5 Tips to Improve Your 60-Yard Dash

As discussed in the 60-Yard Dash: A Case Study post, the 60 is not the most applicable test of “speed” for baseball players, but it is one that will likely be around for a long time. The sprint has many qualities to be optimal; including power, strength, stability, flexibility, and plain old good movement. Without assessing someone for strengths and limitations here are 5 tips to improve your 60-yard dash.

1) Hip Flexor Mobility

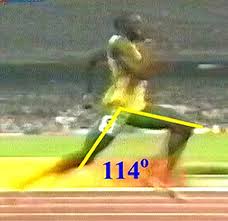

Hip flexors will often be tight and limit the amount of hip extension your leg can get. Increasing hip extension will allow you to naturally increase your stride length. If you can increase stride length without over-striding, you will cover more ground and have need less strides to complete the sprint.

Hip flexors will often be tight and limit the amount of hip extension your leg can get. Increasing hip extension will allow you to naturally increase your stride length. If you can increase stride length without over-striding, you will cover more ground and have need less strides to complete the sprint.

Quad/Posas-Hip Flexor Stretch- hold for 60 sec, while flexing the down leg glute as hard as possible.

2) Hamstring Mobility

Having good hamstring mobility will allow you to naturally extend your leg further in front of you than with poor hamstring mobility. This will again add to your stride length cutting down on the amount of strides needed.

Spider lunge with hamstring floss 10x

3) General Lower Body Strength

Squat, lunge, deadlift, sled push, and farmer’s walks all teach how to put force into the ground and will bring up base strength. Aim for a squat and deadlift of 1.5-2x bodyweight is a great place to start.

4) Specific Lower Body Strength

Single leg hip thrusters are almost the exact same mechanics as running. Squatting and deadlifting are great tools to teach general force production, but single leg hip thrusters are a better tool to apply force in the posterior direction with nearly identical mechanics as a sprint.

3-10 sets of 5-15 reps

5) Specific Lower Body Power

Repeated power with force in the posterior direction is going to carry over to sprint performance seamlessly. Acceleration, the most difficult phase to decrease in short sprints, is directly effected by the amount and quickness of the force that can be placed into the ground—exactly what the single leg trip jump reveals. Use this as your primary measuring stick in training to see if you have become more powerful.

Conclusion

There is no substitute for practicing (and video taping!) 10 and 60-yard dashes to improve your performance, but these tips will leave you more flexible, stronger, and most importantly, FASTER.

The 60-Yard Dash: A Case Study

The 60-yard dash is often one of the first quantitative tests scouts at both the college and professional levels wish to see performed well.

This test has been deeply engrained into the dogma of baseball, while science and many coaches believe that there are better options. The 60-yard dash tests acceleration, top speed, and maintenance of top speed over 180 total feet. In general, baseball is a sport of acceleration and deceleration, not top speed. Regardless of it’s applicability many coaches and scouts use it as a gauge of athleticism and should at least be a consideration for athletes wanting to been seen as competitive. Here’s a case study to show how we address improving speed.

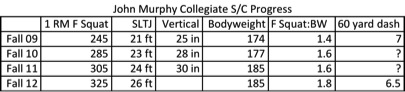

As an incoming freshman shortstop at Sacred Heart University, John Murphy had a 7-7.1 60-yard dash. With a front squat max of 245 and a vertical jump of 25 inches his power and strength was considered average to below average for SHU’s program.

My favorite test for both power and asymmetries is the single leg triple jump (SLTJ). The test is performed by standing on one leg and making 3 consecutive broad jumps on the same side while remaining in control. The goal is to jump as far away from the starting point while sticking each landing. When there is a side-to-side discrepancy of over a foot I investigate deeper to see if we are dealing with strength deficit or something more structurally.

Scoring an average of 21 feet on each side puts John right in the middle of a team average of 22, nothing special to say the least. The ability to apply force into the ground and accelerate your body forward gives us a nice picture of single leg power and a large carryover to running.

As you can see in the chart, as the years progressed, John’s squat, single leg triple jump, vertical jump, and front squat to bodyweight ratio make improvements every year. Increasing relative strength compared to bodyweight and teaching how to increase force production once movement dysfunctions are addressed will consistently increase speed— more importantly acceleration.

An interesting fact to note when looking at the data is that John’s junior year is when he really took his diet to the next level. When dealing with athletes of all levels it clicks at different times. Sometimes this has to do with whom they spend the majority of their time with and sometimes it just takes time to see the light at the end of the tunnel with a goal. Either way, John honed in on his diet by adding about 10 lbs of muscle and dropping a few of fat, again increasing his potential to produce force and become faster.

By John’s senior campaign he had been clocked as low as 6.5 in his 60 and was easily the most powerful athlete in his program. Looking back at his freshman year 21 foot triple jump (7 feet per jump) and increasing it to 26 feet (~8 ½ feet per jump) is a very large difference. This effectively lengthens his stride without changing his mechanics and drops 3-5 strides or ground contacts during his 60-yard dash, dramatically decreasing his time to plus speed in the eyes of MLB organizations.

When training athletes, strength coaches often forget the goal of athletic performance. Our job in the weight room is to help minimize or prevent injury, increase movement efficiency, increase overall strength, and increase force production in a way that it relates to our athlete’s events. You can see we did not test vertical jumps in 2012 because after the past 6 years I have come to realize that the carry over to baseball or other athletic development is much larger with the triple jump gave me lots of qualitative and quantitative data to use in our programming compared to vertical jump data.

Tips to Increase Acceleration Speed

-Video tape and practice your 10-yard dash. Use the video to get your current time and work to improve it. Once your 10-yard dash goes down, your 60 will drop dramatically.

-Increase your front squat max to 1.7-2x bodyweight with solid depth.

-Minimize fat mass and optimize muscle mass. Murph has had his bodyfat as low as 4.5%. By carrying minimal fat mass all weight is functionally producing force.