How To Stop UCL Injuries: The 90MPH Formula

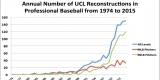

Those familiar with my work know I believe we can stop much of the UCL epidemic with proper screening, training, and logical progressions for athletes.

Camp, C. L., Conte, S., D’Angelo, J., & Fealy, S. (2017). Epidemiology of Ulnar Collateral Ligament Reconstruction in Major and Minor League Baseball Pitchers: Comprehensive Report on 1,313 Cases. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine, 5(7 suppl6).

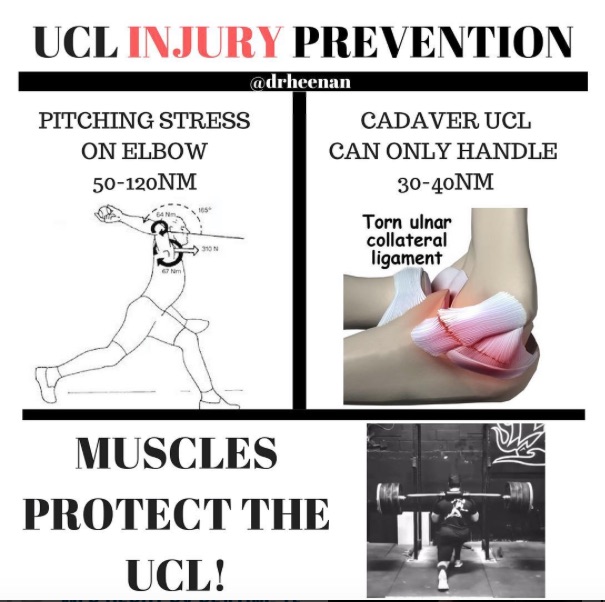

Looking at the current research on valgus stress levels that the ulnar collateral ligament is up to 3 times weaker than the amount of force is exerted on a throw with a baseball.

Based on our current understanding that a UCL cannot alone handle the force that throwing a baseball puts on it, we can make the case for muscular size and strength (within the specificity of the throwing motion) as main factors that protect the UCL from being strained or torn.

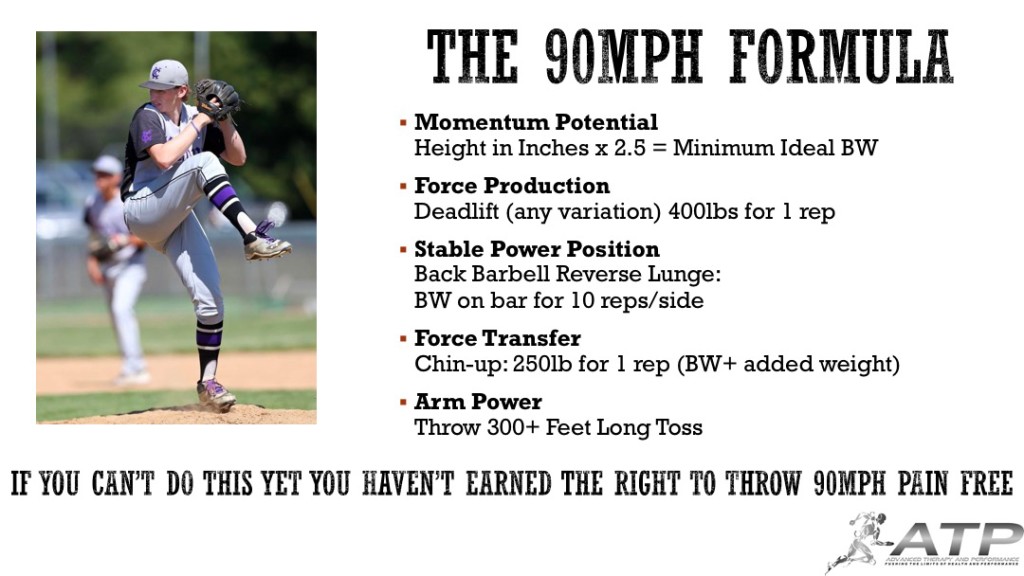

With 1100 baseball players having tested the criteria of the 90MPH Formula and only having 2 reported cases where an athlete could hit the metrics of the formula and needed UCL reconstruction (worth noting neither of these were our athletes local or remote clients). We have had close to 50 as of this post that reported unable to hit the parameters and had UCL reconstruction. Although the collection of the data was not done in a formalize setting, we are working on a formalized study so we can draw better correlations with quality research.

With all of these data points, we can start to draw correlations:⠀

-If you can hit the metrics, you can throw 90mph (or harder).

-If you can’t hit the metrics but can throw 90mph, you are exponentially more likely for an elbow or shoulder injury (UCL surgery most often reported).

⠀

Correlation to increased velo (in order):

1) bodyweight

2) reverse lunge

3) chin-up

4) deadlift

⠀

Correlation to decrease risk of injury (in order):

1) chin-up

2) reverse lunge

3) deadlift

4) bodyweight

⠀

My current thoughts:

-Long toss is still an underrated tool.

-Weighted balls should be used minimally prior to mastering a reverse lunge with your bw on the bar and 10 perfect bodyweight chin-ups.

-Optimal bodyweight is 2.75-3.25 x height in inches

-A 1.5x bodyweight reverse lunge is likely a replacement for 10 reps with bodyweight on the bar.

-Position players that reverse lunge 1.75x bodyweight (1rm) can run a 6.5 or less if they incorporate hill sprints and plyos as they are reaching those levels of strength.

-PO don’t sprint enough to have those strength gains carry over to elite level speed.

-Reverse lunges seem to be HIGHLY correlated to mound velocity, exit velocity, and 10/20/40/60 yard dash times.

-People seem to think I only like reverse lunges which is untrue. There are a ton of ways to increase your reverse lunge. Use what you need to get the reverse lunge to increase.

-Squatting (esp a true box squat) offer a ton of pros to getting you stronger and more athletic, they just don’t correlate to increased velo or decreased sprint times as well as lunges.

-Most high level athletes can achieve many of these numbers with one solid year of training year round. And yes, if you are not training year round I think you are going to spin your wheels for most of your career.

-Deadlift doesn’t seem to correlate well to injury prevention, but I do see a great value for it in terms of force production and adapted muscle mass. However, a 600lb deadlift doesn’t mean you should throw 110mph.

We may not have all the answers, but these correlations should allow athletes, coaches, and parents to utilize the above information in a progressive manner to start to reduce the UCL surgery epidemic we are seeing.

YOU MUST EARN THE RIGHT TO THROW HARD AND STAY HEALTHY!

Move Fast, Throw Hard, Live Well- Little League Curveballs and Youth Weight Training

This weeks post I am going to share a readers question and my response about weight training his younger athlete. If you have a question you would like answered feel free to shoot me an email.

Enjoy!

Q:

What would you recommend for a 13 yr old 7th grader, honestly? I am not wanting him to do more than hi-rep, bodyweight exercises at most. He’s 5’9” (and growing), 110 lbs. throws pretty hard – has a nice arm, and I want to keep that intact. Staring the travel ball with a good, established organization in IL this year…what are your thoughts on throwing curve balls, if taught by a former pro pitcher, etc? (I am leery of that).

A:

As I said in the webinar, if you can play organized sports, you can train (and its safer!). High rep stuff is fine, but that’s where we usually see injuries because of fatigue and poor form. Moderate weights would be a better option for him. Move well and then move higher weights.

Here is my take on youth curveballs; research wise if it’s being taught properly (mechanically efficient) there is not a huge chance of injury. That being said, there are a ton of bad coaches out there (not that his is bad–I have no idea), but being a former pro doesn’t automatically qualify you to be a “good” or well researched coach.

From what I have seen in the rehab and coaching world, poor progression of throwing (jumping up in intensity or mainly volume) too quickly leads to lots of issues. The kids who throw “too many curveballs” are usually the kids who cant compete with just a fastball. And as I have written about before, skipping on fall/winter baseball is a must.

At this point in my career, if my child was a pitcher in little league I would encourage fastball and change up location and speed, that alone will keep batters off balance. Once they start shooting through puberty (13-15 years), I would let them play with curveballs with a coach that is highly qualified. I grew up with a coach who said “never two curves in a row” for both practice and play. Great rules to help set-up hitters and stave away from overuse.

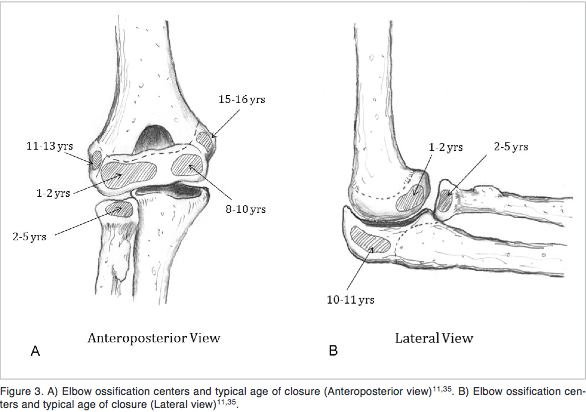

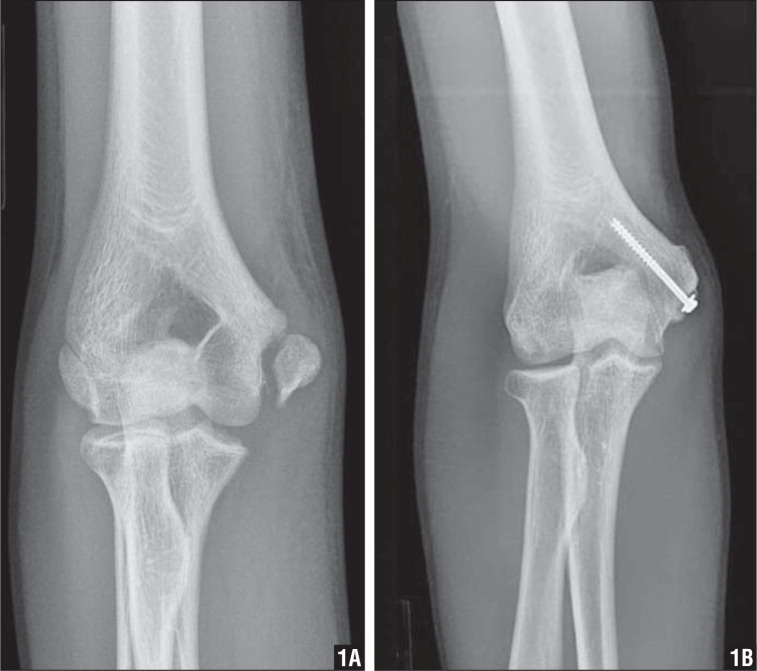

The image attached is a visual of when portions of the arm ossify. The medial epicondyle is the last to fully fuse and we should always proceed with caution.

On the other hand, Phil Rosengren does a great job at expressing why he thinks kids should be tough the curveball at a younger age. To be frank, I don’t disagree with any of his points. And to Phil’s credit, every athlete he has sent me has never had an elbow pathology.

Many people are racing for their kids to be on ESPN in the LLWS. I think they are racing the wrong race. I’ve had the opportunity to work with many kids whom have been on ESPN before the age of 13… some of what they are dealing with mentally are so unfathomable it’s disgusting. Not to mention some of the injuries I’ve seen especially from the “best” players on those teams.

Should My Son Play Fall Baseball?

Early specialization — the practice of playing a single sport for most of the year and foregoing the opportunity to play other sports — is an increasingly popular strategy in the United States. In my experience, this is especially true for baseball, gymnastics, hockey, and soccer. For parents of baseball players, the first question on the road to early specialization is often, “should my son play fall ball?” I offer the following thoughts to help answer this difficult question.

Little League Baseball

Before focusing on Little League baseball in particular, it is helpful to revisit the goals of youth sports in general according to Hedstrom and Gould:1

- Learning and developing physical skills

- Appreciating the value of fitness

- Building a sense of belonging among one’s peers

- Acquiring sport skill for leisure

- Stimulating physical and emotional growth

- Cultivating a sense of self-worth

- Developing social competence

- Building morals and personal integrity

- Learning to cope with failure**** Added by Josh

Little Leaguers experience morphing of the humeral joint (the bone that runs from the shoulder to elbow) as a result of the throwing motion. This adaptation becomes more significant as a player matures physically and begins to throw harder and more often. These changes in the arm lead to more external rotation of the shoulder, which in turn allows a player to throw harder as he gets older.2

A follow-up study questioned pitchers ten years after pitching in Little League. The researchers questioned the former Little Leaguers about injury, which was defined as elbow surgery, shoulder surgery, or retirement due to throwing injury. Pitchers who pitched 100 innings or more were 350% more likely to be “injured” than their counterparts who threw fewer innings in a years time. I would submit that all of these “injuries” were traumatic, as they either ended or directly affected the careers of the players in question.3

For simplicity’s sake, I will exclude the throwing variables caused by playing catcher, playing on multiple teams, throwing with friends, and participating in practices, scrimmages, and warm-ups from the following example. This example also assumes that a pitcher will throw six innings every three games, as this is the “normal” workload for a Little League pitcher.

Westport Little League:

- Spring Regular Season: 20 games or 40 innings pitched

- Summer District Play: 13 games or 26 innings pitched

- Summer Regional Play: 4 games or 8 innings pitched

- Little League World Series: 6 games or 12 innings pitched

- Total: 43 games or 86 innings pitched

Fall Baseball: 8 games or 24 innings (assuming a pitcher will throw 3 inn. a week)

Total: 51 games or 110 innings

To me, these numbers make clear that a Little Leaguer who pitches approximately six innings per week, plays competitively all summer and continues to play fall baseball will reach that 100 inning number and have a markedly higher risk for serious injury or ending their career.

High School

A study by Dr. James Andrews and his staff surveyed two groups of pitchers with an average age of 18. One group had no history of elbow or shoulder pain lasting longer than two weeks; the second group consisted of pitchers who had either shoulder or elbow surgery due to overuse from pitching. The pain-free pitchers averaged 5 ½ months of competitive baseball per year, while the group that required surgery averaged eight. The results of the study reveal that pitchers who pitch competitively eight months per year are 500% more likely to require shoulder or elbow surgery.

High school baseball pitchers in the northeast may have a slight advantage over their southern counterparts, as the seasons in the northeast are shorter (assuming the pitcher does not have access to a dome in the winter). Northeast baseball is normally played competitively for seven months — from April to August with fall ball in September and October — while southern baseball has virtually no offseason. Thus, the abbreviated season in the northeast protects pitchers from overexertion, while the clement weather in the south, though seemingly a blessing, exposes pitchers to a greater risk of injury.

But I need to play more baseball to get better!

Before worrying about a child’s improvement in a given sport, the child’s health and well-being must be considered. Especially in youth sports, parents and coaches have an obligation to monitor their athletes’ physical and mental health. Indeed, experts have observed that “early specialization is associated with a range of negative consequences affecting physical, psychological, and social development.”4 In addition to keeping athletes healthy, the goal of youth athletics should be to allow each player to fulfill his potential and play as long as he desires.

Even so, it is absolutely true that practice is necessary to progress and become elite in a sport. Scott Kaufman speaks on this subject in his book The Complexity of Greatness: Beyond Talent Or Practice.5

Kaufman also notes that children who play multiple sports are better “learners” because they can utilize their prefrontal cortex more efficiently than single sport youths. Experience in a variety of sports gives an athlete a larger “pool” of skills to draw on when attempting a new sport. One of my favorite examples of this is a former athlete of mine, Dave Boisture. Dave was an all-state quarterback who also played baseball and basketball in high school and eventually played outfield in college. Dave’s “pool” of athleticism was large because he was a stellar multi-sport athlete who learned to run, throw, jump, dodge opponents, adapt to field conditions, and play well under pressure. The following video shows Dave making an incredibly athletic catch while running up an inclined outfield in the high-stakes environment of an NCAA Regional Tournament game.

Dave’s holistic approach to baseball and sports in general was clear during our initial fall testing last year. During testing, each player receives a sheet to fill out which includes position. Dave wrote “athlete” instead of “outfield,” the expected response. Dave’s understanding of himself as an athlete, rather than merely a baseball player, allows him to employ the full array of athletic skills that he has learned over the years. This versatility in turn makes Dave indispensable to his team.

Final Thoughts

Besides the fact that the research shows a direct correlation with extra months of competitive baseball and a significantly higher surgery/drop out rate, I am not a fan of fall baseball in its current format. Normal seasons have players practicing and playing 4-6 times per week, while fall ball often has zero or one practice per week with two to four games on the weekend. Most kids don’t throw or prepare themselves for the games during the week, and take the mound as they would during their summer seasons. In my opinion, this lack of consistent practice and preparation during the fall season is dangerous regardless of the number of innings the pitcher has thrown in the spring and summer months.

I also object to the exploitative nature of many fall leagues. Before I receive all sorts of hate mail, please understand that I am speaking in generalizations and that I appreciate that many programs “get it.” However, I know for a fact that many leagues feel that fall ball is necessary to raise more revenue and make ends meet. I also know that many programs exploit this opportunity to tell players and parents that a kid must play fall ball to keep up with their peers and be considered for an organization’s spring or summer programs. Such programs do a disservice to their players not only ethically but also athletically, as this approach limits players’ athletic growth and increases their risk of career-ending injury.

The research presented in this post deals primarily with pitchers, but I recommend limiting all baseball players to competitive spring and summer seasons only. Playing other sports and practicing baseball skills on the side will allow an athlete to progress as much as early specialization, but it involves a much smaller risk of overuse.

Anecdotally, there is no question to what the correct answer is. Every professional baseball player I have ever worked with was a multi-sport stud in high school. In the rehab setting, I have seen an increasing number of injuries that correlate well to the research and are directly linked to fall baseball.

Related Articles

http://www.kevinneeld.com/2011/hockey-development-resistance

http://www.ericcressey.com/your-arm-hurts-thank-your-coaches

Citations

1. Hedstrom R, Gould D. Research in youth sports: Critical issues status. White Pap Summ Exist Lit. 2004. Available at: http://hollistonsoccer.net/image/web/coaches/CriticalIssuesYouthSports%20(2).pdf. Accessed October 9, 2013.

2. Mair SD, Uhl TL, Robbe RG, Brindle KA. Physeal changes and range-of-motion differences in the dominant shoulders of skeletally immature baseball players. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2004;13(5):487–491. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2004.02.008.

3. Fleisig GS, Andrews JR, Cutter GR, et al. Risk of Serious Injury for Young Baseball Pitchers A 10-Year Prospective Study. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(2):253–257. doi:10.1177/0363546510384224.

4. Baker J, Cobley S, Fraser‐Thomas J. What do we know about early sport specialization? Not much! High Abil Stud. 2009;20(1):77–89. doi:10.1080/13598130902860507.

5. Ford PR, Hodges NJ, Williams AM. CREATING CHAMPIONS THE DEVELOPMENT OF EXPERTISE IN SPORT. Complex Gt Talent Pr. 2013:391.